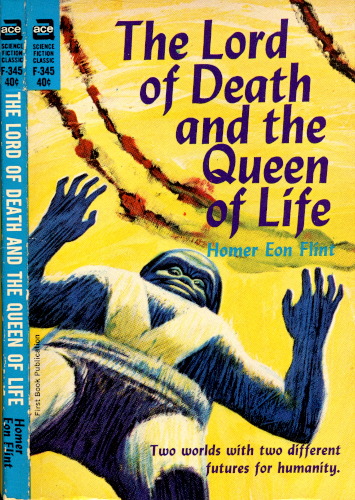

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life

by Homer Eon Flint

PART I

THE DISCOVERY

I

THE SKY CUBE

The doctor, who was easily the most musical of the four men, sang in acheerful baritone:

The geologist, who had held down the lower end of a quartet in hisuniversity days, growled an accompaniment under his breath as heblithely peeled the potatoes. Occasionally a high-pitched note or twocame from the direction of the engineer; he could not spare much windwhile clambering about the machinery, oil-can in hand. The architect,alone, ignored the famous tune.

"What I can't understand, Smith," he insisted, "is how you draw theelectricity from the ether into this car without blasting us all tocinders."

The engineer squinted through an opal glass shutter into one of thetunnels, through which the anti-gravitation current was pouring. "If youdidn't know any more about buildings than you do about machinery,Jackson," he grunted, because of his squatting position, "I'd hate tolive in one of your houses!"

The architect smiled grimly. "You're living in one of 'em right now,Smith," said he; "that is, if you call this car a house."

Smith straightened up. He was an unimportant-looking man, of mediumheight and build, and bearing a mild, good-humored expression. Nobodywould ever look at him twice, would ever guess that his skull concealedan unusually complete knowledge of electricity, mechanisms, and suchpractical matters.

"I told you yesterday, Jackson," he said, "that the air surrounding theearth is chock full of electricity. And—"

"And that the higher we go, the more juice," added the other,remembering. "As much as to say that it is the atmosphere, then, thatprotects the earth from the surrounding voltage."

The engineer nodded. "Occasionally it breaks through, anyhow, in theform of lightning. Now, in order to control that current, and prevent itfrom turning this machine, and us, into ashes, all we do is to pass thejuice through a cylinder of highly compressed air, fixed in this wall.By varying the pressure and dampness within the cylinder, we canregulate the flow."

The builder nodded rapidly. "All right. But why doesn't the electricityaffect the walls themselves? I thought they were made of steel."

The engineer glanced through the dead-light at the reddish disk of theEarth, hazy and indistinct at a distance of forty million miles. "Itisn't steel; it's a non-magnetic alloy. Besides, there's a layer ofcrystalline sulphur between the alloy and the vacuum space."

"The vacuum is what keeps out the cold, isn't it?" Jackson knew, but heasked in order to learn more.

"Keeps out the sun's heat, too. The outer shell is pretty blamed hot onthat side, just as hot as it is cold on the shady side." Smith seatedhimself beside a huge electrical machine, a rotary converter which henext indicated with a jerk of his thumb. "But you don't want to forgetthat the juice outside is no use to us, the way it is. We have to changeit.

"It's neither positive nor negative; it's just neutral. So we separateit into two parts; and all we have to do, when we want to get away fromthe earth or any other