THE SEMANTIC WAR

By BILL CLOTHIER

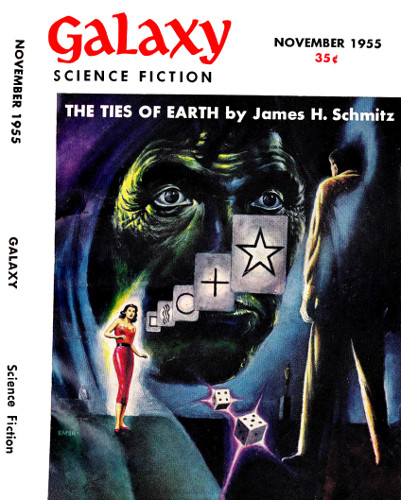

Illustrated by WES

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction November 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Perhaps there have been causes for slaughter

just as silly as this was—but try to find one!

The rain pours down chill out of a sullen sky. My pace quickens as Itry to regain the relative warmth and shelter of the cavern before Ibecome thoroughly drenched. I cannot afford to catch a cold. All aloneas I am and with no medicine, I would stand too great a chance of aquick death. These lowering Oregon skies still hold traces of namelessdisease in their writhing cloud tendrils. I am not just afraid ofa cold. That would only be the key for some other malady to use andstrike me down forever.

I see the cave up ahead and feel a sense of contentment as I draw nearand then duck inside its stony mouth. The rain hisses without, butinside it is dry. There is a heavy cow-hide hanging on a peg in thewall and I take it down and wrap it around me. Soon I will be warm.Once more I may stave off my ultimate end.

Sometimes I wonder why I wish to put it off. Certainly, according to myold standards, there is no point in living. But somehow I feel that themere fact of living is justification in itself. Even for such a life asmine.

I didn't always feel this way. But then circumstances change and peoplechange with them. I changed my circumstances more than myself, but Ihad no alternative. So now I exist.

I suppose I should be content. After all, I am alive and, in my ownsimple way, I enjoy life. I can remember people who asked nothing morethan to be allowed to live—to exist. Ironically enough, I alwaysconsidered them sub-normal. I felt that a man should strive to dosomething that would not only perpetuate the happiness of his ownlife but that of his fellow-men. Something that would make life morebeautiful, and easier, and more kind.

It was with this feeling that I applied myself as a student ofphilosophy at Stanford University. And the strengthening of this samebelief led me to take up teaching and embrace it as the only way ofobtaining genuine happiness. My personal philosophy was simple. Iwould learn about life in all its real and symbolic meanings and thenteach it to my pupils, each of whom, I felt sure, were thirsting forthe knowledge that I was extracting from my cultural environment. Iwould show them the meaning behind things. That, I felt, was the key tosuccessful living.

Now it seems strangely pathetic that I should have essayed such animpossible task. But even a professor of philosophy can be mistaken andbecome confused.

I remember when I first became aware of the movement. For years, we hadbeen drilling certain precepts into the soft, impressionable heads ofthose students who came under our influence. Liberalism, some calledit, the right to take the values accumulated by society over a periodof hundreds of years and bend them to fit whatever idea or act wascontemplated. By such methods, it was possible to fit the mores to thedeed, not the deed to the mores. Oh, it was a wonderful theory, onethat promised to project all human activities entirely beyond good andevil.

However, I digress. It was a spring morning at Berkeley, California,when I had my first inkling of the movement. I was sitting in my officegazing out the window and considering life in my usual contemplativefashi